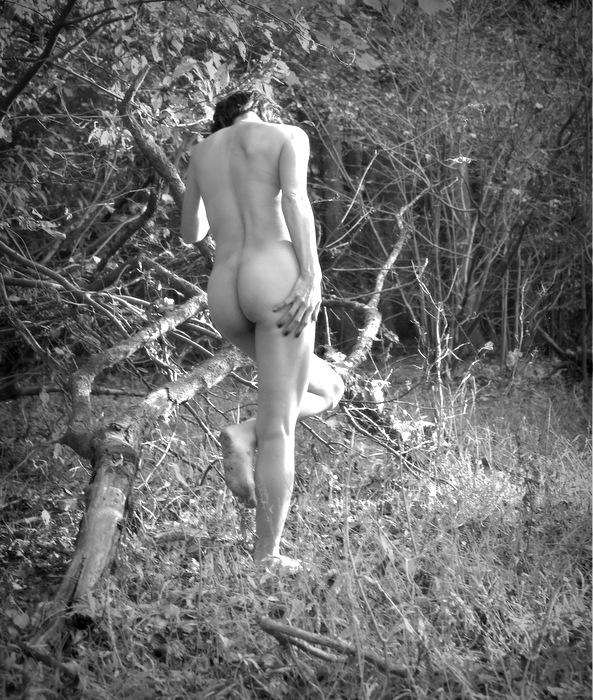

Photo : in Okutama 2019.12

Introduction

The relationship between nature and humanity has been a subject of philosophical contemplation for centuries. From ancient mythologies and religious texts to modern environmental ethics, the dynamic interplay between humans and the natural world has inspired diverse perspectives. This essay explores the philosophical dimensions of this relationship, examining how different traditions and thinkers have conceptualized nature and humanity, the ethical implications of our interactions with the environment, and the contemporary challenges we face in fostering a sustainable coexistence.

Ancient Philosophies: Harmony and Dominion

In many ancient cultures, nature was revered and considered sacred. Indigenous traditions often viewed the natural world as a living entity, imbued with spiritual significance. For instance, Native American philosophies emphasize the interconnectedness of all life forms and the importance of living in harmony with nature. Similarly, Eastern philosophies like Taoism and Buddhism advocate for a deep respect for nature, seeing humans as part of a larger, interdependent ecosystem.

In contrast, Western philosophical traditions have often depicted nature as something to be controlled and mastered. The Judeo-Christian tradition, as interpreted in the Book of Genesis, grants humans dominion over nature, encouraging its exploitation for human benefit. This perspective laid the groundwork for the development of science and technology, which enabled humans to manipulate and transform their environment on an unprecedented scale.

Enlightenment and the Rise of Modernity

The Enlightenment era brought about a significant shift in the human-nature relationship. Philosophers like René Descartes and Francis Bacon championed a mechanistic view of the natural world, emphasizing the use of reason and empirical methods to understand and control nature. Descartes’ famous dictum, “I think, therefore I am,” underscores the separation of the human mind from the natural world, positioning humans as distinct and superior beings.

This mechanistic and anthropocentric view justified the industrial revolution’s exploitation of natural resources, leading to significant environmental degradation. The belief in human progress and the potential for limitless growth overshadowed concerns about the long-term impacts on the planet. As a result, the modern era has been marked by a growing estrangement from nature, manifesting in urbanization, pollution, and the depletion of natural habitats.

Romanticism and the Reassertion of Nature’s Value

In reaction to the industrial revolution’s excesses, the Romantic movement of the 18th and 19th centuries sought to reestablish a connection with nature. Romantic poets and philosophers like William Wordsworth, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau celebrated the beauty and sublimity of the natural world. They criticized the dehumanizing effects of industrialization and advocated for a return to a simpler, more harmonious way of life.

Thoreau’s experiment at Walden Pond epitomizes the Romantic ideal of living in close communion with nature. His writings reflect a deep appreciation for the intrinsic value of the natural world and a recognition of the moral and spiritual benefits of such a relationship. This perspective laid the foundation for modern environmentalism, emphasizing the need to preserve and protect nature for its own sake, rather than merely for its utility to humans.

Environmental Ethics and the Question of Sustainability

The 20th century saw the emergence of environmental ethics as a distinct philosophical field. Thinkers like Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, and Arne Naess developed new frameworks for understanding our moral obligations to the environment. Leopold’s “land ethic” proposes that humans should see themselves as part of a larger ecological community, with responsibilities to maintain the health and integrity of the land. Carson’s seminal work, “Silent Spring,” highlighted the detrimental effects of pesticides on the environment, sparking the modern environmental movement.

Arne Naess, the founder of deep ecology, argued for a radical shift in our perception of nature. He advocated for an ecocentric worldview, where the intrinsic value of all living beings is recognized, and humans are seen as one species among many. This perspective challenges the anthropocentric biases that have historically dominated Western thought and calls for a profound rethinking of our relationship with the natural world.

Contemporary Challenges and the Future of Human-Nature Relations

Today, the relationship between nature and humanity is at a critical juncture. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental pollution pose existential threats to both the planet and human civilization. The Anthropocene, a term used to describe the current geological epoch characterized by significant human impact on the Earth, underscores the urgency of addressing these issues.

Philosophers and environmentalists argue that a sustainable future requires a fundamental transformation in how we perceive and interact with nature. This involves embracing principles of sustainability, resilience, and ecological justice. It also calls for an integration of indigenous knowledge systems and a recognition of the rights of nature, as seen in legal innovations like Ecuador’s constitutional recognition of the rights of Mother Earth.

Conclusion

The philosophical exploration of the relationship between nature and humanity reveals a complex and evolving interplay. From ancient reverence to modern exploitation, and from Romantic appreciation to contemporary environmental ethics, our understanding of this relationship has undergone significant changes. As we face unprecedented environmental challenges, it is imperative to draw on diverse philosophical traditions to foster a more sustainable and harmonious coexistence with the natural world. By reimagining our place within the broader ecological community, we can work towards a future that respects and preserves the intricate web of life that sustains us all.

Title: “Nature and Nudity: Contrasts between Japanese Traditional Culture and Western Interpretations”